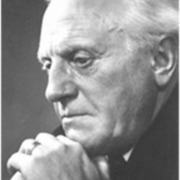

Pär Lagerkvist (1891–1974)

Author of Barabbas

About the Author

Swedish novelist, poet and playwright Par Lagerkvist was born on May 23, 1891 in Vaxjo, Sweden. He attended the University of Uppsala briefly, but did not complete a degree. His first book was published in 1912, the same year he left the University. In 1913 Lagerkvist moved to Paris. He lived show more abroad, mainly in France and Italy, for many years, and even after returning to Sweden, he traveled frequently in Europe. In his earlier writing, Lagerkvist was often bleakly pessimistic. His strong opposition to totalitarianism was voiced in the plays Victor in the Darkness and The Man without a Soul. In the 1940s, however, his focus shifted, and his writing began to explore religious and moral themes, such as the struggle between good and evil or reconciliation with God. Works from this period include The Sibyl, The Death of Ahasuerus, Herod and Mariamne, and The Dwarf. Although he is now probably best known for The Dwarf, which was first published in the 1940s, Lagerkvist's first international success came in 1951, with the publication of Barrabas, a story about the life of the biblical character after he, rather than Jesus Christ, was pardoned. Barrabas was translated into several languages, and adapted as both a play and a movie. Par Lagerkvist was named as one of the 18 "immortals" of the Swedish Academy in 1940. Several years later, in 1951, he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. He died in Stockholm on July 11, 1974. (Bowker Author Biography) show less

Disambiguation Notice:

(yid) VIAF:64007846

Series

Works by Pär Lagerkvist

Sagor, satirer och noveller 17 copies

Barabbas / The Dwarf / Dreadful Tales 15 copies

Kämpande ande 9 copies

Hjärtats sånger 9 copies

Järn och människor : noveller 7 copies

Prosa 5 copies

Ordkonst och bildkonst : [om modärn skönlitteraturs dekadans] : [om den modärna konstens vitalitet] (1991) 5 copies

I den tiden - 5 copies

Motiv 5 copies

Han som fick leva om sitt liv 4 copies

The King: A Play in Three Acts 4 copies

Den lyckliges väg 4 copies

Den osynlige : skådespel i tre akter 4 copies

Vid lägereld / Pär Lagerkvist 4 copies

Dikt i utvalg 4 copies

Maailmas võõrsil 4 copies

Hemmet och stjärnan 3 copies

Den befriade människan 3 copies

Ospite della realta, Il sorriso eterno, Il nano, La sibilla, La morte di Assuero, Pellegrino sul mare, La Terra Santa (1979) 2 copies

The Clenched Fist 2 copies

KUOLLEET, JOTKA ETSIVÄT JUMALAA 2 copies

Genius 2 copies

Literary art and pictorial art : on the decadence of modern literature : on the vitality of modern art (1991) 2 copies

Povestiri amare 2 copies

Sång och strid 2 copies

Valda sidor 2 copies

Krvnik i druge priče 1 copy

Obras completas Tomo 1 1 copy

La Sibila 1 copy

enano, El 1 copy

Himlens hemlighet 1 copy

Antologia do conto moderno — Author — 1 copy

EL ENANO 1 copy

Rabelj / Bodeln 1 copy

Opere 1 copy

Barabba e altre opere 1 copy

Ben 1 copy

Eight Swedish poets 1 copy

Två sagor om livet 1 copy

Bedste Fortællinger 1 copy

Sista mänskan : ett drama 1 copy

Fire and the Hammer, Barabbas, Helen Gould Was My Mother in Law, the Glass of Fashion, the Overloaded Ark, Washington… (1954) — Author — 1 copy

Le opere 1 copy

Sång och strid. [Poems.] 1 copy

Dramatik 1 copy

バラバ 1 copy

Associated Works

Ordens musik : dikter med klang och rytm från Lasse Lucidor till Tage Danielsson : en antologi (1990) — Contributor — 38 copies

Meesters der Zweedse vertelkunst — Author, some editions — 10 copies

Meesters der vertelkunst : zevenendertig verhalen uit de moderne wereldliteratuur (1975) — Contributor — 2 copies

The King [radio play] 1 copy

The Hangman [radio play] 1 copy

Svenske fortællere fra August Strindberg til Harry Martinson — Author, some editions — 1 copy, 1 review

Tagged

Common Knowledge

- Canonical name

- Lagerkvist, Pär

- Legal name

- Lagerkvist, Pär Fabian

- Birthdate

- 1891-05-23

- Date of death

- 1974-07-11

- Burial location

- Lidingö kyrkogård, Lidingö, Sverige

- Gender

- male

- Nationality

- Sweden

- Birthplace

- Växjö, Zweden

- Place of death

- Stockholm, Zweden

- Places of residence

- Växjö, Småland, Sweden (birth)

Stockholm, Sweden (death)

Denmark - Education

- University of Uppsala

- Occupations

- novelist

playwright - Relationships

- Lagerkvist, Bengt (son)

Lagerkvist, Ulf (son) - Organizations

- Svenska Akademien (stol 8)

- Awards and honors

- Nobel Prize (Literature, 1951)

- Disambiguation notice

- VIAF:64007846

Members

Reviews

4.5/5

It amuses me, sometimes, the way people judge books. They'll ban them for epithets, they'll ban them for sex, they'll ban them for witchcraft. More often than not, they'll ban them for raising uncomfortable questions in the minds of children who have not yet been conditioned to follow the proper path. Ignore, and if you cannot ignore, condemn until you can, and if you cannot condemn until you can. Eradicate.

You could ban this book for any of those reasons, much as you could ban the show more Bible. Either one poses much more danger than most literature that is deemed unsafe. For one has resulted in millenia of misguided atrocities and the other is, well. A glimpse of its birth, before all the context, before all the history, before all the rules. Of what could have resulted without it.

The New York Times and Time magazine both referred to it as a parable. I really have to wonder how seriously they took it. It's true that it's not that long, and has religions underpinnings. The 'conveying a truth, religious principle, moral lesson, or meaning' part, though. To put it succinctly, in comparison to this 'parable', nihilism seems vastly more definitive, even encouraging. At least there's an end goal with that.

I will admit to bias, seeing how I was raised Catholic without once grasping the concept behind it all. The question has always fascinated me, though. The meaning of existence. And what a broad field it is! Sophisticated existentialism, misinformed agnosticism, misinterpreted atheism. The hydra of faith. It's all very fascinating, really. To see what extensive lengths humanity has gone in its attempt to reconcile the matter of its wandering in the world. All the shields it has built up between it and the dark.

If this book doesn't make you question whatever shield you have chosen, I would be worried. It doesn't matter that this is framed within the context of one of many religions. It is a human story, subject to the facts of life, the whims of fate, and the maelstrom of the mind. Ultimately, it is cruel, and strange, and will not divulge its secrets, for the truth is that it has no secrets to divulge. What it has is a chain of events that could mean one thing, or another, unless perhaps you missed a lesson here, or heard something incorrectly there, and maybe that person really wasn't the right one you should have listened to, or it was that one happenstance that really messed things up, and if it wasn't for that one specific moment in time you'd know exactly what you were supposed to do, and how things were going to happen, and what it all meant.

Chitterings in the void.

You know what, go ahead and think that this is a parable. Settle on some kind of conclusion, at least, and get it out of your head. It's not conducive to living, this kind of talk. Banning is a bit much, but temperance. Yes. Temperance is a must. show less

It amuses me, sometimes, the way people judge books. They'll ban them for epithets, they'll ban them for sex, they'll ban them for witchcraft. More often than not, they'll ban them for raising uncomfortable questions in the minds of children who have not yet been conditioned to follow the proper path. Ignore, and if you cannot ignore, condemn until you can, and if you cannot condemn until you can. Eradicate.

You could ban this book for any of those reasons, much as you could ban the show more Bible. Either one poses much more danger than most literature that is deemed unsafe. For one has resulted in millenia of misguided atrocities and the other is, well. A glimpse of its birth, before all the context, before all the history, before all the rules. Of what could have resulted without it.

The New York Times and Time magazine both referred to it as a parable. I really have to wonder how seriously they took it. It's true that it's not that long, and has religions underpinnings. The 'conveying a truth, religious principle, moral lesson, or meaning' part, though. To put it succinctly, in comparison to this 'parable', nihilism seems vastly more definitive, even encouraging. At least there's an end goal with that.

I will admit to bias, seeing how I was raised Catholic without once grasping the concept behind it all. The question has always fascinated me, though. The meaning of existence. And what a broad field it is! Sophisticated existentialism, misinformed agnosticism, misinterpreted atheism. The hydra of faith. It's all very fascinating, really. To see what extensive lengths humanity has gone in its attempt to reconcile the matter of its wandering in the world. All the shields it has built up between it and the dark.

If this book doesn't make you question whatever shield you have chosen, I would be worried. It doesn't matter that this is framed within the context of one of many religions. It is a human story, subject to the facts of life, the whims of fate, and the maelstrom of the mind. Ultimately, it is cruel, and strange, and will not divulge its secrets, for the truth is that it has no secrets to divulge. What it has is a chain of events that could mean one thing, or another, unless perhaps you missed a lesson here, or heard something incorrectly there, and maybe that person really wasn't the right one you should have listened to, or it was that one happenstance that really messed things up, and if it wasn't for that one specific moment in time you'd know exactly what you were supposed to do, and how things were going to happen, and what it all meant.

Chitterings in the void.

You know what, go ahead and think that this is a parable. Settle on some kind of conclusion, at least, and get it out of your head. It's not conducive to living, this kind of talk. Banning is a bit much, but temperance. Yes. Temperance is a must. show less

I really liked this one!

Historical fiction, set in Renaissance-era Italy, with squabbling city-states and courtly intrigues as the backdrop. The narrator, a dwarf kept as a curiosity by a local lord, has rejected all connections to humanity, and views everything and everyone else with barely-concealed hatred and disgust. Absolutely no-one he’s ever met has treated him in any other way than as a despicable non-human, and so he keeps himself aloof, separate from the accursed human race.

The show more narrator is unapologetically and just so delightfully evil. Early on in the book, to establish his character, Lagerkvist has him kill a kitten, just to hurt the child whose pet it is. As the novel progresses, and his lord’s ambitions soar, he delights in wreaking underhanded havoc, revels vicariously in crude bloodshed, and spews his indiscriminate revulsion at any and all.

It’s one of those books where the main character would be an awesome villain in someone else’s story, and where the story is one ofthings going from bad to worse for a fascinatingly evil main character, such that you enjoy the destruction while at the same time kinda rooting for and admiring them . show less

Historical fiction, set in Renaissance-era Italy, with squabbling city-states and courtly intrigues as the backdrop. The narrator, a dwarf kept as a curiosity by a local lord, has rejected all connections to humanity, and views everything and everyone else with barely-concealed hatred and disgust. Absolutely no-one he’s ever met has treated him in any other way than as a despicable non-human, and so he keeps himself aloof, separate from the accursed human race.

The show more narrator is unapologetically and just so delightfully evil. Early on in the book, to establish his character, Lagerkvist has him kill a kitten, just to hurt the child whose pet it is. As the novel progresses, and his lord’s ambitions soar, he delights in wreaking underhanded havoc, revels vicariously in crude bloodshed, and spews his indiscriminate revulsion at any and all.

It’s one of those books where the main character would be an awesome villain in someone else’s story, and where the story is one of

The main focus of Barabbas is of course Barabbas himself, but ever since I put the book down over a month ago, I haven't stopped thinking about one particular side character, a small girl with a cleft lip.

Despite being a genuine, good-hearted person, the girl with the cleft lip was kicked out of her house by her mother at a very young age for being "cursed." She lived the rest of her life on the streets of Jerusalem. At one point she entered into a very one-sided relationship with Barabbas, show more who frequently took advantage of her desperate desire to be told by someone, anyone, just once, that they loved her, even if they didn't mean it. She once encountered Jesus, who she firmly believed could heal her.

That was no easy task. After Jesus' death, the girl with the cleft lip attempted to speak at a gathering of a group of disciples, but because she was a little nervous and hard to understand, she made the men uncomfortable and they ignored her. She tried instead to preach to those who had been rejected by society in the same way she had. She spoke to lepers and cripples about the healing power of Christ, and how they, too, would be allowed to enter the house of the Lord. She was overheard by a local blind man, who reported her to the Sanhedrin. She was condemned to death, and she was stoned. Her last words were, "Lord, how can I witness for thee? Forgive me. forgive..."

I don't have a good answer for how to consider such a life. A life filled with unimaginable suffering, and at the end she was still convinced that she had done wrong, or hadn't done enough. Despite spending my entire life within the Church, I couldn't help but read her last words and think that, rather than asking the Lord for forgiveness, it should be the other way around. Jesus should be on his knees, begging to be forgiven for all the torment he put her through. And if that's my reaction, then what could we possibly expect from Barabbas?

This is a man who watched Jesus die on the cross for his sins, in a more direct way than any of the rest of us can claim. At the same time, he saw the purest human being he knew suffer the same fate, all because she believed in Jesus. How does a man in that position come to terms with it all?

Lagerkvist explores this question brilliantly. I won't say any more about it, but I'll be reading this book every Lenten season for the rest of my life. show less

Despite being a genuine, good-hearted person, the girl with the cleft lip was kicked out of her house by her mother at a very young age for being "cursed." She lived the rest of her life on the streets of Jerusalem. At one point she entered into a very one-sided relationship with Barabbas, show more who frequently took advantage of her desperate desire to be told by someone, anyone, just once, that they loved her, even if they didn't mean it. She once encountered Jesus, who she firmly believed could heal her.

"She might well have asked him to cure her of her deformity, but she didn't want to. It would have been easy for him to do so, but she didn't want to ask him. He helped those who really needed help; his were the very great deeds. She would not trouble him with so little."Jesus then approached her and said to her, "You shall bear witness for me."

That was no easy task. After Jesus' death, the girl with the cleft lip attempted to speak at a gathering of a group of disciples, but because she was a little nervous and hard to understand, she made the men uncomfortable and they ignored her. She tried instead to preach to those who had been rejected by society in the same way she had. She spoke to lepers and cripples about the healing power of Christ, and how they, too, would be allowed to enter the house of the Lord. She was overheard by a local blind man, who reported her to the Sanhedrin. She was condemned to death, and she was stoned. Her last words were, "Lord, how can I witness for thee? Forgive me. forgive..."

I don't have a good answer for how to consider such a life. A life filled with unimaginable suffering, and at the end she was still convinced that she had done wrong, or hadn't done enough. Despite spending my entire life within the Church, I couldn't help but read her last words and think that, rather than asking the Lord for forgiveness, it should be the other way around. Jesus should be on his knees, begging to be forgiven for all the torment he put her through. And if that's my reaction, then what could we possibly expect from Barabbas?

This is a man who watched Jesus die on the cross for his sins, in a more direct way than any of the rest of us can claim. At the same time, he saw the purest human being he knew suffer the same fate, all because she believed in Jesus. How does a man in that position come to terms with it all?

Lagerkvist explores this question brilliantly. I won't say any more about it, but I'll be reading this book every Lenten season for the rest of my life. show less

My kids love churches, but not having been brought up religiously, they don't understand any of the iconography. Trying to explain to a six-year-old why they all have statues of this beardy guy slowly dying on a stick has really brought home to me what a hideous and morbid idea Christianity is built on. I understand that some people find it very touching and beautiful, but I find it difficult to see it that way. Telling people that this man went through agony, and then died, on your behalf, show more whether you like it or not, is a heavy load to lay on someone and entails a serious amount of what I suppose psychologists would call guilt.

What's very clever about this book is that Pär Lagerkvist has found a way to examine this idea which works whether or not you believe in the metaphysics: Barabbas, the man acquitted in Jesus's place, is someone in whom the central myth of Christianity is literally true.

They spoke of his having died for them. That might be. But he really had died for Barabbas, no one could deny it!

So the reactions of Barabbas – relief, disbelief, morbid curiosity, survivor's guilt – become a kind of study in what Christian dogma might imply for the human mind. Barabbas can never quite bring himself to believe in Jesus as a divine figure, but, as he says in the novel's most famous passage: ‘I want to believe.’ That conflict is the essence of the book.

Barabbas is a great figure to expand upon, since in the source material he is both crucial and barely mentioned. The Bible gives very few details about him, though there's some suggestion in Luke that he took part in riots in Jerusalem. John, usually the most poetic of the gospels, is disappointingly brief: it simply says, ‘Barabbas was a bandit [λῃστής].’ This gives Lagerkvist great freedom to construct a suitably rough past for him, and the scope to imagine how this one act of being freed might have affected the rest of his life.

In some versions of the Biblical text, Barabbas's full name is ‘Jesus Barabbas’ (which would make sense of Pilate's question to the crowd in Luke – ‘Who would you have me free, [Jesus] Barabbas or the Jesus that is called Christ?’). This may reflect a later mythological tradition, but even so, it points to a deep sense in which the two are equated – indeed, there are serious Biblical scholars who believe that they are one and the same person. This duality is fully explored in Lagerkvist's story, which sees Barabbas go through similar ordeals and, for that matter, end up nailed in the same place.

His state of mind and his state of belief at that point are open to interpretation. It's a very incisive way of looking at the challenges and mysteries of such big topics as atonement, the crucifixtion, and faith – and one which goes to the heart of them in a way that theological texts generally do not. show less

What's very clever about this book is that Pär Lagerkvist has found a way to examine this idea which works whether or not you believe in the metaphysics: Barabbas, the man acquitted in Jesus's place, is someone in whom the central myth of Christianity is literally true.

They spoke of his having died for them. That might be. But he really had died for Barabbas, no one could deny it!

So the reactions of Barabbas – relief, disbelief, morbid curiosity, survivor's guilt – become a kind of study in what Christian dogma might imply for the human mind. Barabbas can never quite bring himself to believe in Jesus as a divine figure, but, as he says in the novel's most famous passage: ‘I want to believe.’ That conflict is the essence of the book.

Barabbas is a great figure to expand upon, since in the source material he is both crucial and barely mentioned. The Bible gives very few details about him, though there's some suggestion in Luke that he took part in riots in Jerusalem. John, usually the most poetic of the gospels, is disappointingly brief: it simply says, ‘Barabbas was a bandit [λῃστής].’ This gives Lagerkvist great freedom to construct a suitably rough past for him, and the scope to imagine how this one act of being freed might have affected the rest of his life.

In some versions of the Biblical text, Barabbas's full name is ‘Jesus Barabbas’ (which would make sense of Pilate's question to the crowd in Luke – ‘Who would you have me free, [Jesus] Barabbas or the Jesus that is called Christ?’). This may reflect a later mythological tradition, but even so, it points to a deep sense in which the two are equated – indeed, there are serious Biblical scholars who believe that they are one and the same person. This duality is fully explored in Lagerkvist's story, which sees Barabbas go through similar ordeals and, for that matter, end up nailed in the same place.

His state of mind and his state of belief at that point are open to interpretation. It's a very incisive way of looking at the challenges and mysteries of such big topics as atonement, the crucifixtion, and faith – and one which goes to the heart of them in a way that theological texts generally do not. show less

Lists

Awards

You May Also Like

Associated Authors

Statistics

- Works

- 132

- Also by

- 19

- Members

- 4,761

- Popularity

- #5,269

- Rating

- 3.9

- Reviews

- 90

- ISBNs

- 237

- Languages

- 24

- Favorited

- 30

Charts & Graphs

Loading